- 2.0 Where do you get your supply of food?

So let’s look at a realistic scenario that you can relate to. You live in the city. You depend on your local supermarket to bring

food to you. This happens by magic. You have no idea how these things are done day to day because it doesn’t concern

you. You take it for granted that you go to the supermarket and it is stocked up with what you need. You just have to make

sure you have money to buy these things. Suddenly, you lose your job. No problem! You look for another one. But now you

can’t find one because there are millions like you looking for a job. So perhaps the government helps you with money. But

now more people lose their jobs. And yet more... The government cannot give money away for free to everyone. If it could, it

would do so today. No one works, but everyone receives a paycheck and spends it on… On what if no one is producing

anything? Why would an agricultural corporation produce food for you if there are no profits? And even if there are profits,

under the instant scenario these profits mean nothing. They have no value. Profits are great when you can use the money

to buy goods and services. In the instant economic arrangement nobody works or produces anything. They just get a

paycheck from the government. Why would anyone work at the agricultural complex? Our artificial economy is based on

trade, not on welfare. If there is nothing to trade except money for food, the agricultural firm has no reason to produce

anything.

So you’re out of a job together with millions of others and you go to your local supermarket. But the economy has collapsed

and the producers and distributors of food have not produced or distributed. They are out of a job too, remember? So the

shelves are empty. Now what? What are you going to eat? What are you going to hunt in the asphalt jungle? An alley cat?

Your neighbor’s dog? How will billions of urbanites across the planet feed themselves when the global economy collapses?

The day that the global economy crashes, our carrying capacity instantly reverts to the hunter-gatherer level, but in a new

setting. The typical proletarian is stranded in the city, with nowhere to go (because transportation and fuel have come to a

stop), and with nothing to eat. The ecological pyramid has suddenly inverted on you and we have the many chasing after

the few (Figs. 5 and 6). The lake has shrunk to a puddle overnight and will shortly dry up completely. This is exactly what

happened to the dinosaurs.

- ________________________________________________________________________________________

- Last modified 04/20/08

- Copyright © by Nila Gaede 2008

| Food has gradually become a vanishingly small percentage of Man’s economy |

| Adapted for the Internet from: Why God Doesn't Exist |

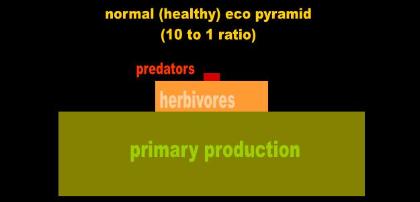

Fig. 6 Overturning the ecological pyramid |

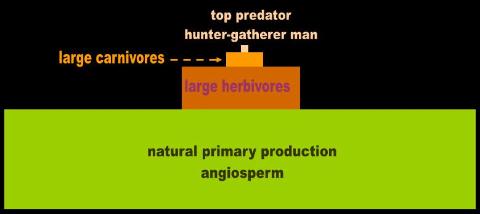

| A ‘normal’ pyramid maintains a 10 to 1 food ratio between lower and upper levels. Man was a hunter-gatherer for over 100,000 years and became the undisputed top predator when the Neanderthals became extinct. During most of this time Man thrived in a natural economy: a ‘normal’ ecological pyramid. Much biomass is underutilized. |

- 1.0 We have distanced ourselves exponentially from the only thing we need to stay alive: food

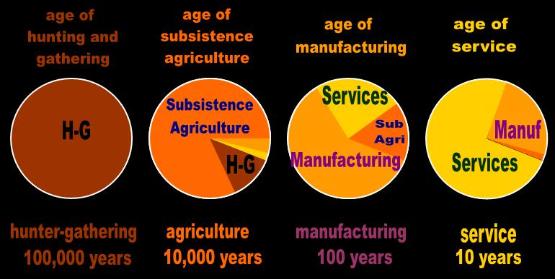

A more ominous long-term trend that escaped both Morgan and Engels is that food progressively becomes a tinier segment

of our artificial economy. For over 100,000 years, humans were parasitic hunter-gatherers, living off the fat of the land.

Throughout this lengthy period, our economy – like that of any other animal – consisted only of food. One day, about 10,000

years ago, we discovered agriculture, and shortly after learned to domesticate farm animals. However, we didn’t remain long

in this subsistence-agriculture stage. Some farmers quickly realized that they could trade their surplus for certain goods and

services that were produced by specialists. Commerce and division of labor were born, and this is what we normally identify

with the beginnings of civilization. We could thus define civilization in this context as the period in Man’s socio-economic

development in which he distances himself from the only thing that keeps him alive: food. Throughout the agricultural phase

food gradually declined as a percentage of the world economy, but more dramatically towards the end of the 18th Century

when the Industrial Revolution came about. This phase lasted an order of magnitude less than the previous one – perhaps at

most 200 years – when a new, silent revolution shifted us to the service economy. So allow me to run all that by again in fast-

forward while rounding off liberally just to make a point. We lived 10 years as hunter-gatherers, 10 as farmers, 10 as

manufacturers, and barely 10 as service sector proletarians (Figs. 1 and 2). The raw data shows that our global economic

structure has evolved exponentially.

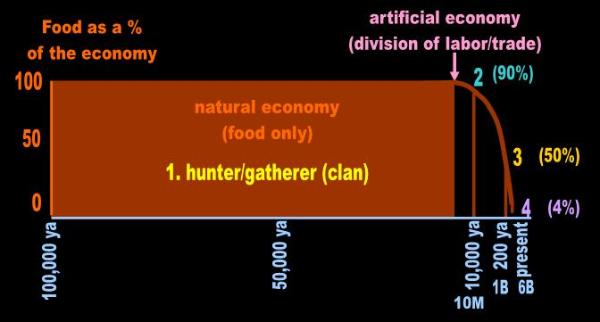

If we now speculate that some time around the start of commercial agriculture 90% of the economy consisted of food, by

the time the Industrial Revolution came along in Europe this number had to have dropped quickly. I know this because

today global agriculture is a paltry 4% of World GDP! Compare this against the importance of the service sector: 64% of

GDP of the global economy. The service percentage is continuing to rise at the expense of agriculture and manufacturing

as we speak. These ominous developments have distanced more and more humans from the most vital of resources: food.

Fig. 5 The carrying capacity through the ages: Geological stages leading to the extinction of Man |

Fig. 1 Mode of production through the ages |

1. A natural economy consists solely of hunter/gatherers. It can only support a relatively

plant biomass. Meanwhile, diseases and predators cap the populations yet at a lower limit.

higher population than hunter gathering would allow. Man can plan his food requirements in advance. Still, population is capped by the amount of food, the only commodity available.

by manufacturing and later by services. What this does is generate a variable carrying capacity, which can theoretically be unlimited. The carrying capacity in this highly developed artificial economy is no longer a function of food. Manufacturing and population develop a symbiotic relation. One grows and fuels the growth of the other. Goods and services expand in proportion to population and vice versa. As merely another industrial commodity, food simply follows the demographic progress, but is not what triggers population to grow (i.e., people don’t have more children because there is more food).

Goods and services would have continued to grow exponentially as shown by the dotted line. However, since population stagnates, so does the global supply of goods and services. When the global service economy reaches its peak, the carrying capacity instantly reverts to being a function of food. We have a natural economy in an urban setting. The service economy crashes. It surprises urban Man entirely isolated from primary production. Food is produced artificially in response to demand. Urban Man discovers a painful lesson. The supply of food is not a function of population, but of genuine wealth (as opposed to money). No wealth, no food. The collapse of the urban service economy offers the agricultural manufacturer no incentive to produce and distribute food. |

| The pie charts show the changing face of the global economy on a macro scale. 100,000 years ago there were only hunter-gatherers. Their economy consisted solely of food. The situation changed little when we initially converted to agriculture, but we discovered division of labor and soon other line items began to appear. By the time we got to manufacturing, services were growing strong and subsistence agriculture together with hunter-gathering became anachronisms. The percentages at the bottom are not precise. Their purpose is simply to highlight that the entire process is exponential. Today, service is crowding out all other categories. So what’s next? What other economic activity or line item can the Man move into? Is the service economy going to continue for the next million years? Can we attain an economy that is 100% service? The first thing this chart destroys is the idiotic notion the establishment has perpetuated that history repeats itself. In the context of economics, the relativistic economist wishes you to believe that business comes in cycles. The pie chart shows that this is not true for long term trends. We are NOT going back to manufacturing and even less to subsistence farming! |

| then agriculture |

| now services |

As if this weren’t enough, there is another ratio that should make you wonder what the relativistic economists have running

through their sterile minds. Throughout all these thousands of years, without anyone noticing, we inadvertently changed the

ratio of the top predator to the availability of food from 10-to-1 to 1-to-1 (Figs. 3 and 4). There is enough food on the planet

today to feed 6 billion people for a very short time. We don’t store food for seven years like the biblical pharaohs. On paper

we have at most three months [2] worth of reserves. We have placed our pawns and rooks in indefensible positions. From a

strategic perspective, we have already lost the game. In a few more moves, Mother Nature will checkmate Man. All we need is

an economic collapse to trigger the event.

Fig. 2 The day Man lost control of the only necessity of life: The history of food |

Food was essentially the only component of Man’s economy for over 100,000 years. After

he discovers commercial agriculture, food decreases gradually as a percentage of the

artificial economy, a trend that accelerates after industrialization. The Age of Agriculture

lasts for only about 10,000 years and the industrial phase for just over 100. Today, food

has dropped to barely 4% of the global economy. In the U.S. it is even worse, constituting

an ominous 0.7 % of GDP! If we remove non-edibles (cotton, wool, forestry, etc.) the

percentage is even smaller. This low number is a tribute to Man’s extra-ordinary efficiency.

As little as 3% of the labor force of the U.S. is allocated to agriculture!

he discovers commercial agriculture, food decreases gradually as a percentage of the

artificial economy, a trend that accelerates after industrialization. The Age of Agriculture

lasts for only about 10,000 years and the industrial phase for just over 100. Today, food

has dropped to barely 4% of the global economy. In the U.S. it is even worse, constituting

an ominous 0.7 % of GDP! If we remove non-edibles (cotton, wool, forestry, etc.) the

percentage is even smaller. This low number is a tribute to Man’s extra-ordinary efficiency.

As little as 3% of the labor force of the U.S. is allocated to agriculture!

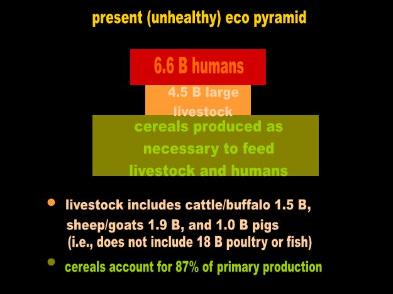

Civilized humans grossly distort the natural

ecological pyramid. Large terrestrial carni-vores

become irrelevant and practically extinct. Artificial

selection ensures a more efficient production and

transfer of animal and plant biomass. The 10 to 1

ratio gradually declines. Artificial production

replaces natu-ral production and becomes a

function of demand (i.e., population). Agriculture

gra-dually works its way to become an insig-

nificant part of Man’s artificial economy. As a

result of these trends, the population of the ‘top

predator’ grows disproportionately with respect

to resources.

ecological pyramid. Large terrestrial carni-vores

become irrelevant and practically extinct. Artificial

selection ensures a more efficient production and

transfer of animal and plant biomass. The 10 to 1

ratio gradually declines. Artificial production

replaces natu-ral production and becomes a

function of demand (i.e., population). Agriculture

gra-dually works its way to become an insig-

nificant part of Man’s artificial economy. As a

result of these trends, the population of the ‘top

predator’ grows disproportionately with respect

to resources.

Near-future Man ceases artificial primary

production and herding for lack of economic

incentives. Production is controlled by cor-

porations which take business decisions founded

on profits rather than on biological needs. Vast

number of humans suddenly find themselves

isolated from vital resources. Law and order break

down. Man ravages what is left. The last stage of a

mass extinction is cannibalism. (Note: In reality,

the size of the box for ‘near-future Man’ is about

as large as the box for ‘civilized Man’ in the

previous illustration. What has contracted

drastically is the food supply.)

production and herding for lack of economic

incentives. Production is controlled by cor-

porations which take business decisions founded

on profits rather than on biological needs. Vast

number of humans suddenly find themselves

isolated from vital resources. Law and order break

down. Man ravages what is left. The last stage of a

mass extinction is cannibalism. (Note: In reality,

the size of the box for ‘near-future Man’ is about

as large as the box for ‘civilized Man’ in the

previous illustration. What has contracted

drastically is the food supply.)

5

4

2

1

Module main page: The day the global economy collapses, it will be the end of Man

Pages in this module:

- 1. This page: Food has gradually become a vanishingly small percentage of Man’s economy

2. The last stage of a mass extinction: Cannibalism

- The point of these back-of-napkin analyses is that the tapering population curve leads to economic stagnation and

economic stagnation leads to joblessness. The urban proletariat has in a short time nothing to trade for something he

needs: food. Today, food is produced by corporations and only for profits. If the urbanite has nothing of value to offer,

the agriculturalist has no incentive to plow and harvest for him. The crash of the urban economy means the crash of

our carrying capacity as well because in our artificial economy food is just another industry (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3 A healthy pyramid |

| A normal or healthy pyramid thrives through most of the history of a class of animals (dinosaurs, mammals, etc.). The ratio between trophic levels is around 10 to 1, meaning that the tonnage of the next upper level is one tenth of that of the lower level. |

Fig. 4 An unhealthy pyramid |

| A pyramid that is in trouble is one where predators outnumber herbivores and where herbivores have a very tight ratio with primary production. Food production is so efficient today that we have reserves for about three months. The number of species we depend on for meat (specialization) has also dropped. We clear jungles and forests to make way for cereals to feed livestock and humans. The 10 to 1 ratio no longer exists. An economic collapse is all it takes to disintegrate this fragile system. |

The first thing this line of reasoning shows is that we do not need nuclear weapons or climate change or diseases to wipe

out our species. The agent that not a single paleontologist, anthropologist, ecologist, biologist, or economist considers when

pondering mass extinction is food. If anything, food is mentioned as an afterthought and not as the strategic factor.

The second thing this mechanism brings up is the startling realization that we have worked our way to a very precarious

position. We are 6.6 billion humans, living on an island called Earth, with nowhere to go, and with a 3 month worth supply

of food. Of course, the economist will say that this is just a measure of Man's efficiency, which is true. The issue is that

agricultural corporations produce this vital necessity upon demand and for a profit. Without profits, the agriculturalist has

no incentive to produce food. Therefore, the health of the global economy is no longer an issue that only affects stock

market investors. Now it is a life or death situation for every human on Earth. If the global economy happens to collapse

tomorrow, billions of people are suddenly stuck in cities around the world without any food. This is a significant departure

from the hunting-gathering days when humans were few and had direct access to abundant sources. We have gradually

converted food into a scarce resource.

Yet another thing we realize in retrospect is that these trends were entirely predictable and unavoidable. It was predictable

that Man would discover agriculture, that he would industrialize and mechanize in order to make his life more comfortable,

and that he would work his way to a service economy. It is also now predictable that the human population will attain ZPG

some time in this century. If our artificial economy depends on demand and demand is ultimately a matter of more humans,

ZPG is an ominous milestone and seals the fate of our race. Certainly, only an idiotic economist from the Chicago School of

Economics would suggest that a more or less constant number of humans will be living for the next million years in a service

economy. The difficulties we are experiencing in the global markets today are not of a cyclical, but rather of a structural nature.

We will never go back to 19th Century style, labor-intensive manufacturing. We will never go back to Roman-style, slave-labor

agriculture. We will never go back to Cro-Magnon style hunter-gathering. The relativistic economists should stop reading

Friedman and get a history book.